In the vast landscape of modern manufacturing, forging and CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining stand as two shining stars, each radiating unique brilliance. These processes serve as fundamental pillars in shaping industrial products across nearly all sectors—from aerospace and automotive to medical devices and electronics. While both techniques contribute to component manufacturing, they differ significantly in principles, methodologies, applications, and the characteristics of their final products.

I. Forging: Precision Through Pressure

1. Definition and Historical Context

Forging represents one of humanity's oldest yet most dynamic manufacturing processes, with roots tracing back to early civilization. At its core, forging involves applying substantial pressure to metal workpieces, inducing plastic deformation that alters their shape and dimensions to achieve desired components. This pressure—whether impact or static—typically requires specialized equipment like forging hammers or presses.

The evolution of forging technology spans millennia. Ancient civilizations employed basic forging techniques using stone hammers and wooden mallets to craft tools and weapons. Advancements in metallurgy introduced bronze and iron implements, elevating forging capabilities. Medieval European blacksmiths perfected the craft, producing durable armor and weaponry. The Industrial Revolution brought steam power and electricity, revolutionizing forging equipment and productivity. Today's forging technology comprises a sophisticated system of diverse processes and machinery tailored to various production needs.

2. Principles and Techniques

Forging capitalizes on metal's plastic deformation capacity. When subjected to force, metals undergo elastic deformation (reversible) until exceeding their yield point, at which plastic deformation (permanent) occurs. Forging exploits this property to reshape workpieces while simultaneously refining their internal grain structure—enhancing density, uniformity, and ultimately the component's strength, toughness, and fatigue resistance.

Forging operations classify by temperature:

-

Hot Forging:

Conducted above the metal's recrystallization temperature, facilitating significant deformation with lower resistance. Ideal for large, complex parts like engine crankshafts and connecting rods.

-

Cold Forging:

Performed at or near room temperature, requiring greater pressure but yielding superior dimensional accuracy and surface finish while increasing strength and hardness. Common for precision components like gears and fasteners.

-

Warm Forging:

Operates between hot and cold forging temperatures, balancing formability with precision. Suitable for moderately complex, mid-sized components.

3. Advantages and Limitations

Forging offers distinct benefits:

-

Enhanced Mechanical Properties:

Optimized grain structure improves strength, toughness, and fatigue resistance.

-

Material Efficiency:

Minimizes waste, boosting utilization rates and cost-effectiveness.

-

Mass Production Suitability:

High throughput accommodates large-scale manufacturing demands.

-

Versatile Geometry:

Capable of producing diverse shapes, including complex configurations.

However, forging presents some constraints:

-

High Tooling Costs:

Specialized dies, particularly for intricate designs, require substantial investment.

-

Precision Limitations:

Generally less precise than machining, often necessitating secondary operations.

-

Surface Finish:

Typically requires additional processing to achieve desired smoothness.

4. Industrial Applications

-

Aerospace:

Manufactures high-strength components like engine parts and landing gear.

-

Automotive:

Produces durable drivetrain elements including crankshafts and transmission gears.

-

Heavy Machinery:

Creates stress-resistant components such as large bearings and industrial gears.

-

Energy Sector:

Fabricates corrosion-resistant valves and piping for oil/gas applications.

-

Power Generation:

Manufactures robust turbine blades and generator rotors.

II. CNC Machining: Precision Engineering

1. Definition and Technological Evolution

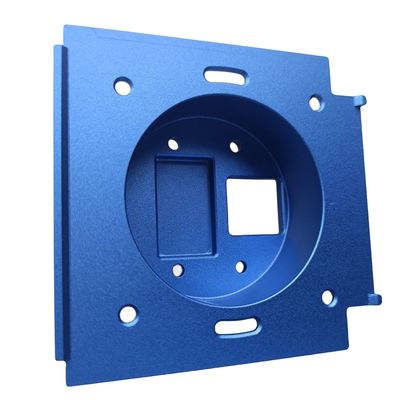

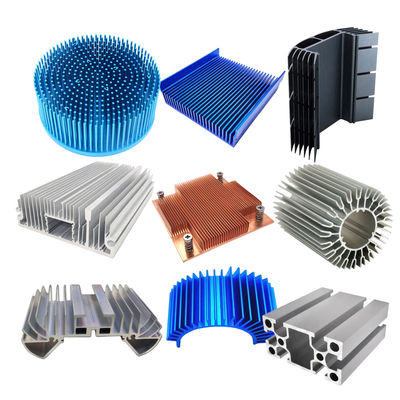

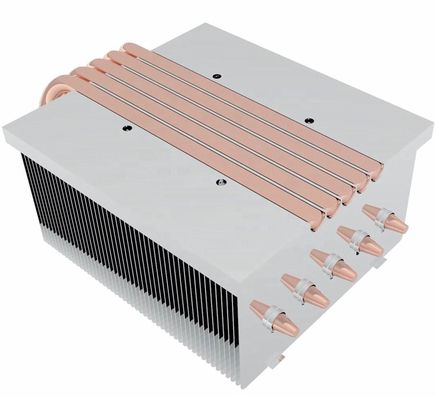

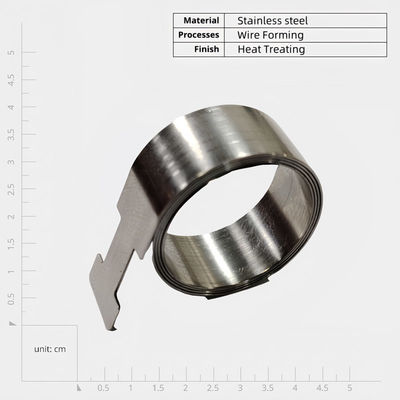

CNC machining represents a subtractive manufacturing process where computer-controlled tools selectively remove material from solid blocks (metal, plastic, or composite) to achieve precise geometries. Compared to conventional machining, CNC offers superior accuracy, efficiency, and flexibility for complex part production.

The technology emerged in the 1950s when MIT developed the first numerically controlled milling machine. Advancements in computing transformed early punch-tape systems into today's direct digital controls, dramatically improving precision and throughput. Modern CNC encompasses diverse machining methods and equipment configurations tailored to varied production requirements.

2. Principles and Processes

CNC machining relies on programmed toolpath trajectories that guide cutting implements to remove material systematically. The workflow typically involves:

-

Design:

Creating 3D models via CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software.

-

Programming:

Converting designs into machine instructions using CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) software.

-

Setup:

Loading programs, selecting tools, and securing workpieces.

-

Machining:

Executing material removal operations per programmed instructions.

-

Inspection:

Verifying dimensional accuracy and surface quality.

Primary CNC techniques include:

-

Milling:

Rotating cutters remove material to create features like slots, pockets, and complex contours.

-

Drilling:

Spinning bits produce holes of various diameters and depths.

-

Turning:

Stationary tools shape rotating workpieces to manufacture cylindrical components.

-

Grinding:

Abrasive wheels achieve ultra-fine surface finishes and tight tolerances.

3. Advantages and Limitations

CNC machining provides significant benefits:

-

Exceptional Precision:

Computer control enables micron-level accuracy and repeatability.

-

Design Flexibility:

Accommodates intricate geometries and rapid design iterations.

-

Automation:

Reduces manual intervention while enhancing productivity.

-

Material Versatility:

Processes metals, plastics, and composites alike.

However, CNC presents some drawbacks:

-

Capital Intensity:

High equipment costs demand substantial investment.

-

Programming Complexity:

Requires skilled personnel for efficient toolpath generation.

-

Material Waste:

Subtractive nature generates more scrap compared to forming processes.

-

Throughput Limitations:

Less economical than forging for high-volume production.

4. Industrial Applications

-

Medical Devices:

Manufactures implants and surgical instruments requiring exceptional surface finishes.

-

Electronics:

Produces enclosures and circuit board components with tight tolerances.

-

Aerospace:

Fabricates airframe components and turbine blades demanding exacting specifications.

-

Automotive:

Machines engine blocks and transmission parts requiring precise mating surfaces.

-

Tooling:

Creates molds for plastic injection and die casting applications.

III. Key Differentiators

Understanding these processes' fundamental distinctions enables informed selection:

1. Material Properties and Strength

Forging's compressive forces align internal grain structures along stress directions—analogous to wood grain—enhancing strength, toughness, and fatigue resistance. This proves particularly advantageous for components enduring cyclic or impact loading. CNC machining cannot alter base material microstructure, making forged parts superior for demanding mechanical applications.

2. Precision and Complexity

CNC machining excels in dimensional accuracy and geometric intricacy, achieving micron-level tolerances and smooth surface finishes ideal for precision assemblies. Forging suits simpler geometries often requiring secondary machining for fine details.

3. Production Efficiency and Cost

Forging proves more economical for high-volume production of robust components despite higher initial tooling costs. CNC offers greater flexibility for low-volume or prototype work but becomes less cost-effective at scale due to slower cycle times and greater material waste.

4. Material Compatibility

CNC accommodates broader material selections including non-metallics, whereas forging primarily benefits metallic alloys like steel, aluminum, and titanium.

IV. Hybrid Manufacturing Approaches

Many applications combine both processes—forging near-net shapes followed by CNC finishing—to leverage their respective strengths. This hybrid methodology optimizes mechanical properties while achieving required precision, representing a growing trend in advanced manufacturing.

V. Process Selection Considerations

Optimal manufacturing method depends on:

-

Component material specifications

-

Geometric complexity and tolerance requirements

-

Mechanical performance expectations

-

Production volume and cost targets

VI. Future Outlook

Emerging trends include:

-

Smart Manufacturing:

Integration with IoT and AI for predictive maintenance and process optimization.

-

Sustainability:

Energy-efficient equipment and waste reduction initiatives.

-

Nanoscale Precision:

Advancements in ultra-precision machining capabilities.

-

Advanced Materials:

Adaptation for next-generation composites and alloys.

VII. Conclusion

Forging and CNC machining represent complementary manufacturing paradigms, each excelling in specific applications. Forging delivers superior mechanical properties for high-strength components, while CNC enables unparalleled precision for complex geometries. Hybrid approaches often provide optimal solutions, blending both technologies' advantages. Understanding these processes' capabilities empowers manufacturers to make strategic production decisions aligned with technical and economic objectives.

Your message must be between 20-3,000 characters!

Your message must be between 20-3,000 characters! Please check your E-mail!

Please check your E-mail!  Your message must be between 20-3,000 characters!

Your message must be between 20-3,000 characters! Please check your E-mail!

Please check your E-mail!